In the late afternoon on the day after the 1983 General Election my then girlfriend and I spoke at great length on the (landline) telephone while I was still hungover, sleep deprived and utterly, utterly miserable. An hour or so later she turned up at my door and suggested I needed to "get out the house".

We drove up the Gleniffer Braes and went for a walk. The view of Paisley was as magnificent as always but it did little lighten my mood. At one point the path reached an escarpment with a sharp drop and Christine cautioned, not entirely in jest, that I was not to think about jumping.

The thing was that nothing about what had happened was other than as expected but it didn't make it any easier to bear.

You see elections are important. I'd done pretty much all the marching and rallying and meeting and conferencing on offer over the previous four years to 1983. It was, to be honest, hugely enjoyable. "Everybody" you met hated the Tories. "Everybody" predicted utter catastrophe for the NHS, the Trade Unions, Local Government, poor people in general: everything the Labour Party cared about, if the Tories were returned to power. With, at the time, the additional frisson that there was every prospect of a nuclear war.

Yet we all just stood and watched it happen. The polls said Foot couldn't win but we, at best, believed this could be turned round in the campaign or, at worst, simply disbelieved the polls as bad for (our) morale.

During the day of 12th December I was struck by the enthusiasm of the very many young people shown on twitter engaged in "getting out" the Labour vote in appalling weather. Many, I have no doubt, enthusiastic Corbynistas. It is what they choose to learn from their own experience which will now determine what happens next. For I was so reminded of my younger self.

If they are content to spend another four or five years having a good time marching, rallying, meeting and conferencing, knowing that it will almost certainly come with a massive hangover at the end of it, then Corbynism will continue in form if not in name. With the same, or potentially an even worse, ending in 2024 or 25. All of the 57 varieties of Leninism Corbyn has let (back) in will be quite happy with that, as they do not truly believe in a parliamentary route to socialism anyway. So will be the anti-Semites, for continuity Corbynism means continuity membership. So will the social media panhandlers and the Unite faction around Corbyn's inner circle, who will presumably keep their well paid jobs and disproportionate influence, as indifferent to the wreck of a once great Party as they have been already to the wreck of a once great trade union.

But they are not enough without the (genuinely) idealistic.

The key lies with these new, mainly young, activists. Some I suspect will drift away, daunted by any prospect of turning things round. But others will stay. And hopefully they will not want to repeat the experience of "that" exit poll. Getting to them will be the key to any more mainstream candidate getting the Party back.

But we can't lose sight of the other errors of Corbynism that could as easily have been made by a more centrist leadership. The Party's image has become ridiculously Londoncentric. It is no accident that this is the one part of the Country where we actually gained a seat. But you can't win an election in London alone. As has just been demonstrated, Keir Starmer and Emily Thornberry might have come from humble stock but they are not (today) humble stock. At least in public perception.

I'm not myself persuaded that it "has" to be a woman but I'm certainly of the view that it "has" to be someone with a direct appeal outside the M25. And, Dan Jarvis aside, that leaves the only credible candidates being women.

But it also has to be someone, to use a reference which is hopefully not too anachronistic, who has "The X Factor".

One of the lessons of the election is that while there should be no doubt (NO DOUBT!!!!) who now is the Party of Government, there remains little doubt who is the most likely alternative. Both the Libs and the Tigs crashed and burned. It might yet be the case that the next non Tory Government is not a Labour Government but even if Labour takes the most disastrous of turns in the next three months that is not, I suspect, something that would become apparent until (at least) after the next general election. Yes, on the one hand, the task, in terms of conventional "swing" is an enormous one but on the other, given the volatility of the electorate, it need not be an impossible one. Assuming it has the right message, and messenger, from day one.

And this is where things become difficult, for it is not entirely about politics. But it is entirely about who cuts through as different but not frightening. And on any view that is Jess Phillips. Just as it was once about Barack Obama.

Tuesday, 31 December 2019

Sunday, 8 December 2019

My final election blog: A strangely British Election.

It has been a strangely British election in Scotland.

In 2015 and 2017 the UK General elections were essentially different events north and south of the border.

Here, there were "local" debates with the Scottish Party leaders up front and centre and distinctively different television coverage. That was to some extent the preference of all of the main Scottish Parties. The SNP naturally welcomed an assumption that Scotland was already semi-independent but the other three Parties also had a vested interest. Labour and the Libs assumed that their Scottish "brand" and leader had an appeal beyond the UK franchise. The Tories initially simply wanted to be seen to be "different" here but by 2017 had worked out that they possessed a Scottish leader with a Heineken reach.

That was then however, this is now. Even in two and a half years we have a much changed media. Uniquely Scottish newspapers are in relative decline in relation to the readership of the Scottish editions of their UK based competitors and that does mean that coverage of the election has more of a UK tinge but, more importantly still, the BBC, still most peoples's source of news, has shuffled off much of its Scottish political coverage to a channel literally nobody watches. The SNP should perhaps have been more careful about what they wished for in that regard.

And then there are the specific circumstances of this contest applying to each of the four main Parties. On any view this is not so much a Tory election campaign as a Boris Johnson election campaign and the Scottish Tories have had little option but to buy into that. Johnson has been far more prominent here than either Cameron or May, interestingly directly taking on the nationalist mantra that "the Tories don't care about Scotland". That in turn has rather disguised the fact that the Scottish Tories don't actually have a permanent leader and freed up Ruth Davidson to play the role of a Scottish El Cid, taking the battle to where she wants to go without having to carry the burden of kingship.

Labour has also had to make a virtue of necessity. The absence of any identifiable Scottish leadership has left us with little alternative to Corbyn being here far more than in 2017, although he continues to feature little if at all in local campaign literature. By now the election here for Labour has become a struggle for survival, retaining as many "touching distance" second places as possible. Time will tell if this has worked.

And the Libs, led by a Scottish MP at Westminster, clearly have an interest in promoting her over giving Willie Rennie much more than a bit part this time round.

Finally, we have the SNP. Or should I say Nicola. For the rest of the Nats have been more or less invisible. Nicola seems to be on the UK telly just about every night, not as the voice of independence but as a sort of fantasy, social democratic, candidate for the position of a Remain Prime Minister. I am genuinely at a loss as to the purpose of this, for she is not seeking that position, indeed she is not seeking, at this election, any position at all. It also seems somewhat strange to effectively write off the votes of North East Scotland in pursuit of the votes of south east England.

Anyway, as I say, the net effect of this is that this has been the most British election in Scotland since at least 2010.

And that will have consequence.

It increasingly looks that there is going to be a UK Tory landslide and Tory landslides (or indeed Labour landslides, remember them?) do not pass parts of the country entirely by.

I started my election blogs by pointing out that the opening question at this election should not have been how many seats the Scottish Tories were going to lose lose but rather how many they were going to gain. How the press report matters is entirely a matter for them but I don't think that it is unfair to observe that, purely from the point of view of trade, Scottish political journalists have a vested interest in a narrative that the SNP are still going forward and that a second independence referendum remains very much on the horizon. That might explain why, even now, no-one has really been prepared to dive in to the inviting pool of seats the Tories might pick up. But there are in fact a good number.

And two things particularly favour the Tories this time.

In 2017 there was, in truth, little tactical voting. Where the Tories picked up seats the Labour vote actually went up. Where the Tories got close, and were clearly close, it also remarkably held up. But since then the nationalist cause, on the streets at least, has developed a much more distinctive republican tone, including overt parallels to Irish republicanism. There is a certain section of the electorate who really don't buy into this but who for reasons of class or family history have been previously reluctant to ever vote Tory. My own view however is that these people are open to the Tory call to be "lent" their vote to stop a second independence referendum. Particularly as their objections to nationalism mirror their objections to Corbynism. That's not just my view however, it is pretty much every piece of Tory literature is saying. For a reason.

The second thing which favours the Tories is that they are going to win. And there is a certain logic, with that as a given, that it favours Scotland to have large numbers on the winning side. Playing the sort of role that was probably most famously played in the past by George Younger. But, additionally, if the SNP are not going to hold the balance of power and if there is not going to be another referendum, what exactly, in a Westminster context, is their function? Moaning?

In 1979 the Scottish Tories got 31.4% of the Scottish popular vote. I think they will beat that in 2019.

31.4% brought them 31% of the seats then available (22 of 71). I think that's pretty much where we are now. So my final election prediction? Labour 3; Lib-Dems 5; Tories 18; SNP 33.

In 2015 and 2017 the UK General elections were essentially different events north and south of the border.

Here, there were "local" debates with the Scottish Party leaders up front and centre and distinctively different television coverage. That was to some extent the preference of all of the main Scottish Parties. The SNP naturally welcomed an assumption that Scotland was already semi-independent but the other three Parties also had a vested interest. Labour and the Libs assumed that their Scottish "brand" and leader had an appeal beyond the UK franchise. The Tories initially simply wanted to be seen to be "different" here but by 2017 had worked out that they possessed a Scottish leader with a Heineken reach.

That was then however, this is now. Even in two and a half years we have a much changed media. Uniquely Scottish newspapers are in relative decline in relation to the readership of the Scottish editions of their UK based competitors and that does mean that coverage of the election has more of a UK tinge but, more importantly still, the BBC, still most peoples's source of news, has shuffled off much of its Scottish political coverage to a channel literally nobody watches. The SNP should perhaps have been more careful about what they wished for in that regard.

And then there are the specific circumstances of this contest applying to each of the four main Parties. On any view this is not so much a Tory election campaign as a Boris Johnson election campaign and the Scottish Tories have had little option but to buy into that. Johnson has been far more prominent here than either Cameron or May, interestingly directly taking on the nationalist mantra that "the Tories don't care about Scotland". That in turn has rather disguised the fact that the Scottish Tories don't actually have a permanent leader and freed up Ruth Davidson to play the role of a Scottish El Cid, taking the battle to where she wants to go without having to carry the burden of kingship.

Labour has also had to make a virtue of necessity. The absence of any identifiable Scottish leadership has left us with little alternative to Corbyn being here far more than in 2017, although he continues to feature little if at all in local campaign literature. By now the election here for Labour has become a struggle for survival, retaining as many "touching distance" second places as possible. Time will tell if this has worked.

And the Libs, led by a Scottish MP at Westminster, clearly have an interest in promoting her over giving Willie Rennie much more than a bit part this time round.

Finally, we have the SNP. Or should I say Nicola. For the rest of the Nats have been more or less invisible. Nicola seems to be on the UK telly just about every night, not as the voice of independence but as a sort of fantasy, social democratic, candidate for the position of a Remain Prime Minister. I am genuinely at a loss as to the purpose of this, for she is not seeking that position, indeed she is not seeking, at this election, any position at all. It also seems somewhat strange to effectively write off the votes of North East Scotland in pursuit of the votes of south east England.

Anyway, as I say, the net effect of this is that this has been the most British election in Scotland since at least 2010.

And that will have consequence.

It increasingly looks that there is going to be a UK Tory landslide and Tory landslides (or indeed Labour landslides, remember them?) do not pass parts of the country entirely by.

I started my election blogs by pointing out that the opening question at this election should not have been how many seats the Scottish Tories were going to lose lose but rather how many they were going to gain. How the press report matters is entirely a matter for them but I don't think that it is unfair to observe that, purely from the point of view of trade, Scottish political journalists have a vested interest in a narrative that the SNP are still going forward and that a second independence referendum remains very much on the horizon. That might explain why, even now, no-one has really been prepared to dive in to the inviting pool of seats the Tories might pick up. But there are in fact a good number.

And two things particularly favour the Tories this time.

In 2017 there was, in truth, little tactical voting. Where the Tories picked up seats the Labour vote actually went up. Where the Tories got close, and were clearly close, it also remarkably held up. But since then the nationalist cause, on the streets at least, has developed a much more distinctive republican tone, including overt parallels to Irish republicanism. There is a certain section of the electorate who really don't buy into this but who for reasons of class or family history have been previously reluctant to ever vote Tory. My own view however is that these people are open to the Tory call to be "lent" their vote to stop a second independence referendum. Particularly as their objections to nationalism mirror their objections to Corbynism. That's not just my view however, it is pretty much every piece of Tory literature is saying. For a reason.

The second thing which favours the Tories is that they are going to win. And there is a certain logic, with that as a given, that it favours Scotland to have large numbers on the winning side. Playing the sort of role that was probably most famously played in the past by George Younger. But, additionally, if the SNP are not going to hold the balance of power and if there is not going to be another referendum, what exactly, in a Westminster context, is their function? Moaning?

In 1979 the Scottish Tories got 31.4% of the Scottish popular vote. I think they will beat that in 2019.

31.4% brought them 31% of the seats then available (22 of 71). I think that's pretty much where we are now. So my final election prediction? Labour 3; Lib-Dems 5; Tories 18; SNP 33.

Saturday, 30 November 2019

My fourth election blog: The centre has not held.

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,........

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

W.B. Yeats, The Second Coming (1921)

This was meant to be the election of the centre. Both of the major Parties are in the grip of their wildest extremes. Both are led by figures who are in different ways regarded, even by some of their own members, even indeed by a number of their own candidates, as unfit for the post of Prime Minister. One is absolutely in favour of abandoning that great centrist institution, the European Union, the other at best ambivalent on that matter.

When the election was called there was a real anticipation that not only would the Liberal Democrats flourish, possibly even to the extent of coming second in the popular vote, but that they would be joined in the Commons by a number of "independent" refugees from the two big Parties who weren't, for whatever reason, willing to completely jump the dyke to actual Lib Dem membership.

In the run up to and indeed during the campaign, the Lib Dem cause has been joined by some of the brightest and best of former Labour and Tory centrist MPs and endorsed by former grandees of both big Parties. What possible better circumstance could they have?

Yet it simply has not happened. No-one now suggests they will get anything like the 23% of the popular vote and 57 seats won by Nick Clegg in 2010, when the electorate was otherwise faced with a choice between the far more mainstream Prime Ministerial candidates of Gordon Brown and David Cameron.

Furthermore, the chances of more than one or two of the miscellaneous independents getting elected is vanishingly small. My money would be on none at all.

The reasons for this are many and complex.

The starting point is that this is a quasi-presidential system and while objection can be raised to both Johnson and Corbyn in that role, objection can also be raised to Jo Swinson. I hesitated before writing this for fear of be accused of ageism or, worse, mysoginy, but you cannot avoid the conclusion that this election has came to soon for her. She is is too young, too inexperienced for you to able to close your eyes and imagine her in 10 Downing Street. If I might make a comparison with another political figure, Nicola Sturgeon, that was precisely the calculation that the SNP made when rejecting the idea of Nicola Sturgeon as their leader in 2004. Since then however Ms Sturgeon has been (at least) deputy leader of the SNP for fifteen years. She has had a leading role in in, now, eight Scottish or UK Elections, never mind two referendums. It is that which has honed her into the consummate politician which even her worst enemies would concede she now is.

Jo Swinson has had no such baptism, let alone confirmation. Until six months ago she was a fairly unknown figure and she simply has not had time to grow into a leadership role. It is that, rather than more fundamental personal failings, which has hampered her in this campaign.

But there have been other mistakes by the Lib Dems, most fundamentally on their positioning on Brexit. Whether we like it or not, in June 2016 the British people voted in a referendum to leave the EU. You can't just ignore that. But the Libs essentially proposed/propose to do just that. This was then compounded by suggesting that their initial ambition was to win the election outright. That avoided them having to express a preference between Johnson and Corbyn but left the Party of PR suggesting that c.40% in a General Election would overrule 52% in a referendum. This might have a certain logic if you believe any Brexit is disastrous, so, as the Party of Government, you could never countenance such a happening. It also avoids the absurdity of the Labour position of negotiating a different deal but then possibly campaigning against it in a referendum but it just doesn't/didn't seem fair and raised genuine fears of de-legitimising the democratic process.

In any event, the idea that the Libs could "win" the election, even with miscellaneous independent allies was always absurd. After three weeks of the campaign they have conceded that themselves and are back to arguing for a major role in a hung Parliament. But that then washes them back onto the perilous rocks of choosing between Corbyn and Johnson and in particular the problem that one key target voting group, Tory remainers, are horrified with the idea that Corbyn might gain power on any basis, while a second key group, Labour voters who don't like Corbyn, are equally fearful of Johnson still in number ten. If that wasn't enough, a third key group, those who just want to move on from Brexit, are far from convinced they want another hung Parliament at all.

Not even with the benefit of hindsight, this illustrates the strategic error of the centrist opposition in the last Parliament nailing their colours to the always illusory quest of a second vote rather than offering to work with Mrs May for the softest of Brexits. Now they would argue that offer would not have been accepted but since it was never made we will never know what would have happened if it had. What we do know is that in consequence Theresa May, Philip Hammond, Jeremy Hunt and Amber Rudd have been replaced each by a much more right wing successor who are now on the verge of a Tory landslide.

And that leads me to my final reason for failure, Liberal Democrat sectarianism. They have quite expressly spurned the opportunity to assist their own would be allies. Excepting their rather strange deal with the Greens and Plaid in sixty or so seats, few of these where any of these three Parties have any chance, they have resolved to stand against almost all the centrist independents, withdrawing only against the apparently randomnly chosen Sir Dominic Grieve. They also continue to oppose those surviving centrist candidates of the two big Parties even where that might only assist their hard Brexiteer or mad Corbynista opponent.

I'm going to write further about this after the election but hopefully the Liberal Democrats will finally realise themselves that their most fundamental error of this election is that if the centre is to prosper, it requires the Liberal Democrats (the mistake the Tiggers made in not realising) but it can't comprise the Liberal Democrats alone.

When the election was called there was a real anticipation that not only would the Liberal Democrats flourish, possibly even to the extent of coming second in the popular vote, but that they would be joined in the Commons by a number of "independent" refugees from the two big Parties who weren't, for whatever reason, willing to completely jump the dyke to actual Lib Dem membership.

In the run up to and indeed during the campaign, the Lib Dem cause has been joined by some of the brightest and best of former Labour and Tory centrist MPs and endorsed by former grandees of both big Parties. What possible better circumstance could they have?

Yet it simply has not happened. No-one now suggests they will get anything like the 23% of the popular vote and 57 seats won by Nick Clegg in 2010, when the electorate was otherwise faced with a choice between the far more mainstream Prime Ministerial candidates of Gordon Brown and David Cameron.

Furthermore, the chances of more than one or two of the miscellaneous independents getting elected is vanishingly small. My money would be on none at all.

The reasons for this are many and complex.

The starting point is that this is a quasi-presidential system and while objection can be raised to both Johnson and Corbyn in that role, objection can also be raised to Jo Swinson. I hesitated before writing this for fear of be accused of ageism or, worse, mysoginy, but you cannot avoid the conclusion that this election has came to soon for her. She is is too young, too inexperienced for you to able to close your eyes and imagine her in 10 Downing Street. If I might make a comparison with another political figure, Nicola Sturgeon, that was precisely the calculation that the SNP made when rejecting the idea of Nicola Sturgeon as their leader in 2004. Since then however Ms Sturgeon has been (at least) deputy leader of the SNP for fifteen years. She has had a leading role in in, now, eight Scottish or UK Elections, never mind two referendums. It is that which has honed her into the consummate politician which even her worst enemies would concede she now is.

Jo Swinson has had no such baptism, let alone confirmation. Until six months ago she was a fairly unknown figure and she simply has not had time to grow into a leadership role. It is that, rather than more fundamental personal failings, which has hampered her in this campaign.

But there have been other mistakes by the Lib Dems, most fundamentally on their positioning on Brexit. Whether we like it or not, in June 2016 the British people voted in a referendum to leave the EU. You can't just ignore that. But the Libs essentially proposed/propose to do just that. This was then compounded by suggesting that their initial ambition was to win the election outright. That avoided them having to express a preference between Johnson and Corbyn but left the Party of PR suggesting that c.40% in a General Election would overrule 52% in a referendum. This might have a certain logic if you believe any Brexit is disastrous, so, as the Party of Government, you could never countenance such a happening. It also avoids the absurdity of the Labour position of negotiating a different deal but then possibly campaigning against it in a referendum but it just doesn't/didn't seem fair and raised genuine fears of de-legitimising the democratic process.

In any event, the idea that the Libs could "win" the election, even with miscellaneous independent allies was always absurd. After three weeks of the campaign they have conceded that themselves and are back to arguing for a major role in a hung Parliament. But that then washes them back onto the perilous rocks of choosing between Corbyn and Johnson and in particular the problem that one key target voting group, Tory remainers, are horrified with the idea that Corbyn might gain power on any basis, while a second key group, Labour voters who don't like Corbyn, are equally fearful of Johnson still in number ten. If that wasn't enough, a third key group, those who just want to move on from Brexit, are far from convinced they want another hung Parliament at all.

Not even with the benefit of hindsight, this illustrates the strategic error of the centrist opposition in the last Parliament nailing their colours to the always illusory quest of a second vote rather than offering to work with Mrs May for the softest of Brexits. Now they would argue that offer would not have been accepted but since it was never made we will never know what would have happened if it had. What we do know is that in consequence Theresa May, Philip Hammond, Jeremy Hunt and Amber Rudd have been replaced each by a much more right wing successor who are now on the verge of a Tory landslide.

And that leads me to my final reason for failure, Liberal Democrat sectarianism. They have quite expressly spurned the opportunity to assist their own would be allies. Excepting their rather strange deal with the Greens and Plaid in sixty or so seats, few of these where any of these three Parties have any chance, they have resolved to stand against almost all the centrist independents, withdrawing only against the apparently randomnly chosen Sir Dominic Grieve. They also continue to oppose those surviving centrist candidates of the two big Parties even where that might only assist their hard Brexiteer or mad Corbynista opponent.

I'm going to write further about this after the election but hopefully the Liberal Democrats will finally realise themselves that their most fundamental error of this election is that if the centre is to prosper, it requires the Liberal Democrats (the mistake the Tiggers made in not realising) but it can't comprise the Liberal Democrats alone.

Sunday, 24 November 2019

My Third Election blog. For Labour, Winter is coming

It says everything that today's Panelbase poll giving Scottish Labour a mere 20% was nonetheless greeted with some sense of relief in my Party's ranks. The week before last there were three Council by-elections in Scotland: two in Fife and one in Inverness. The Labour vote fell by 4.3%, 6.9% and, in the only seat where we had much of a vote share to start with, a spectacular 13.%. In the last case, Dunfermline Central, we also managed to go from second place to fourth in one fell swoop.

It is looking increasingly likely Labour will lose every seat we currently hold north of the border excepting the wholly unrepresentative example of the "Labour and Unionist" candidate Ian Murray in Edinburgh South.

This would remain a tragic outcome to me, semi detached though I am from Corbyn's Labour. Not least as several outstanding public representatives will be swept away in the process, never mind that many others who would make outstanding public representatives will never get that opportunity.

It would be fair to say however that Corbyn and his allies wrote off Scotland from the start. Their pivot to supporting or at least allowing a second independence referendum had nothing to do with attracting Labour votes in Scotland but everything to do with attracting SNP votes in a hoped for hung Parliament in the post election period.The Scottish Labour Party was not even as much as consulted in the process and I doubt if this policy shift will feature on a single Labour leaflet north (or indeed south) of the Border.

But it will all, anyway, be in vain, except for leaving us with an immense hangover for the 2021 Holyrood election, as it seems increasingly clear from the UK polls that on 12th December, we are heading for at least a Tory majority and in all probability a Tory landslide.

There will then be an existential choice for the Labour Party. The manifesto consists of little more than a whole list of retail policies aimed, not, in my opinion, even very cleverly, at specific target groups of voters, together with a gigantic wish list of public sector and want to be public sector Trade Union demands. Today's £58Bn overnight "promise" to women in their sixties without even the pretence of knowing how it would be funded is but the most ludicrous example of the former to date, while the straightforward manifesto offer of an immediate pay increase to a select group of workers, whose unions are bankrolling Labour's campaign, borders on the farcical. And don't even get me started on "sectoral collective bargaining".

But there is no doubt the manifesto was greeted with something approaching hysteria in Corbynista circles. It is in truth worthless. Mere words on a piece of paper much of which the leadership circle know themselves has no prospect of being implemented, given that the limit of their electoral ambition is to be the largest Party in a hung Parliament. Anybody think the SNP would ever sign up for the entire country's broadband being within the monopoly hands of the British Government? Or the Libs for pretty much any of this, even if Corbyn himself was sacrificed in pursuit of their support? No, me neither.

But the question is what happens next. For some, a "brilliant" manifesto every five years and four years and ten months of meetings, rallies and protests in between will be an end in itself. "Hobby politics" as someone once described it. The cult of Jeremy will become the cult of Rebecca, or whoever, but otherwise things pretty much carry on as before. Hopefully., at least, with a bit less anti-Semitism.

I wouldn't be at all surprised if that happens. The same Trade Unions most signed up for Corbyn have been content with that pattern of events for their own internal affairs. Declining memberships and declining real world influence or even relevance but still brilliant banners to wave on the occasional, not very well attended, demonstration.

If it does, Labour's only continued function will be to entrench the Tories in permanent power in a way that the Italy's PCI did for nearly fifty years post war for the Italian Christian Democrats. The PCI had even better banners, and bigger, more colourful marches, in the process. They could also call on much better film directors than Ken Loach to document their struggle. A lot of good it did them. Real change only came when the DC destroyed themselves with the corruption absolute power always brings in the end. Even then, continued factionalism between the left and centre simply paved the way for Berlusconi and now, one fears, Salvini.

Well done Jeremy. If you can secure the succession for an acolyte, you will leave a lasting legacy. Where that leaves the rest of us will be the subject of my next blog. I suspect it won't be happy reading either.

It is looking increasingly likely Labour will lose every seat we currently hold north of the border excepting the wholly unrepresentative example of the "Labour and Unionist" candidate Ian Murray in Edinburgh South.

This would remain a tragic outcome to me, semi detached though I am from Corbyn's Labour. Not least as several outstanding public representatives will be swept away in the process, never mind that many others who would make outstanding public representatives will never get that opportunity.

It would be fair to say however that Corbyn and his allies wrote off Scotland from the start. Their pivot to supporting or at least allowing a second independence referendum had nothing to do with attracting Labour votes in Scotland but everything to do with attracting SNP votes in a hoped for hung Parliament in the post election period.The Scottish Labour Party was not even as much as consulted in the process and I doubt if this policy shift will feature on a single Labour leaflet north (or indeed south) of the Border.

But it will all, anyway, be in vain, except for leaving us with an immense hangover for the 2021 Holyrood election, as it seems increasingly clear from the UK polls that on 12th December, we are heading for at least a Tory majority and in all probability a Tory landslide.

There will then be an existential choice for the Labour Party. The manifesto consists of little more than a whole list of retail policies aimed, not, in my opinion, even very cleverly, at specific target groups of voters, together with a gigantic wish list of public sector and want to be public sector Trade Union demands. Today's £58Bn overnight "promise" to women in their sixties without even the pretence of knowing how it would be funded is but the most ludicrous example of the former to date, while the straightforward manifesto offer of an immediate pay increase to a select group of workers, whose unions are bankrolling Labour's campaign, borders on the farcical. And don't even get me started on "sectoral collective bargaining".

But there is no doubt the manifesto was greeted with something approaching hysteria in Corbynista circles. It is in truth worthless. Mere words on a piece of paper much of which the leadership circle know themselves has no prospect of being implemented, given that the limit of their electoral ambition is to be the largest Party in a hung Parliament. Anybody think the SNP would ever sign up for the entire country's broadband being within the monopoly hands of the British Government? Or the Libs for pretty much any of this, even if Corbyn himself was sacrificed in pursuit of their support? No, me neither.

But the question is what happens next. For some, a "brilliant" manifesto every five years and four years and ten months of meetings, rallies and protests in between will be an end in itself. "Hobby politics" as someone once described it. The cult of Jeremy will become the cult of Rebecca, or whoever, but otherwise things pretty much carry on as before. Hopefully., at least, with a bit less anti-Semitism.

I wouldn't be at all surprised if that happens. The same Trade Unions most signed up for Corbyn have been content with that pattern of events for their own internal affairs. Declining memberships and declining real world influence or even relevance but still brilliant banners to wave on the occasional, not very well attended, demonstration.

If it does, Labour's only continued function will be to entrench the Tories in permanent power in a way that the Italy's PCI did for nearly fifty years post war for the Italian Christian Democrats. The PCI had even better banners, and bigger, more colourful marches, in the process. They could also call on much better film directors than Ken Loach to document their struggle. A lot of good it did them. Real change only came when the DC destroyed themselves with the corruption absolute power always brings in the end. Even then, continued factionalism between the left and centre simply paved the way for Berlusconi and now, one fears, Salvini.

Well done Jeremy. If you can secure the succession for an acolyte, you will leave a lasting legacy. Where that leaves the rest of us will be the subject of my next blog. I suspect it won't be happy reading either.

Monday, 11 November 2019

My second election blog: What worries the Nats.

On the face of it the first Scotland wide poll published since the election was called (although its fieldwork pre-dated that) was good news for the SNP. 42% and almost twice the votes of their nearest rivals (The Tories).

But, in truth they have four quite separate worries.

The first is that they are aware of a tendency, that I have already alluded to in my previous blog, for Westminster Scottish polling to overstate their support. They themselves realise that constant references to Westminster as a "foreign" parliament, necessary for their wider project, is hardly a strong point when arguing that their supporters must nonetheless turn out to vote in its elections. The big thing about 2017 was not that the opposition Parties gained lots of votes but rather than the SNP lost them. I wouldn't bet on them having got them back.

The second is that they fear being caught in a pincer. They worry on the one hand about leeching votes to the Lib Dems, who are the "quiet life" Party in Scotland promising "no more referendums" but also promising remain. This will lose them no seats directly to the Libs, except obviously Fife NE, but it certainly, under first past the post, sees them losing seats to others. They also worry however about how their own, now more, far more, than 2017, express commitment to Remain will play with the forgotten 38% of Scottish politics. Those who voted leave in 2016, a good one third of whom at least, by most calculation, had voted Yes in 2014. Brexit wasn't really an issue in Scotland in 2017. It will be this time.

Thirdly, they worry about their closeness to the idea of making Jeremy Corbyn Prime Minister. He is not, by any means, the sole reason for Scottish Labour's current unpopularity. He is, nonetheless, exceptionally unpopular. Almost as much in Scotland as in England. And yet given the way the Nats have positioned themselves, the only way now to ensure he never enters Downing Street is to vote for the Tories or the Lib Dems. I bet, given the chance, Nicola would turn back time to adopt the Jo Swinson position of possible support for a Labour Government but never for one led by Corbyn. Then again, as she juggles the nationalist balls in the air, that might risk losing populist votes elsewhere.

And finally, they worry about the weather. Not really extreme weather that would affect all parties equally but just dreich horrible weather. The SNP are blessed, if that's the right word, by some front line supporters who would, to their credit I suppose, walk five miles barefoot through a snowdrift to cast their votes for "Freedum!" But their leadership are acutely aware that they also have more or less a monopoly of those who, on the day, depending on the day, look out the window and might not feel bothered to vote at all. Roll on the sleet.

Now, there remain lots of things to encourage the Nats. Nobody suggests they won't remain Scotland's largest party on 13th December. They have however set the bar so high for themselves, and the stakes are so high for them, that I suspect Nicola would bite your arm off now if offered the deal of a single net gain on 13th December. For she gets what a single net loss would mean.

But I finish with a telling example. In 2017, I highlighted what I described as "secret seats", meaning seats that no-one thought in play but I believed might change hands. A lot of them then did. So here's my 2019 secret seat. Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch and Strathspey. SNP vote 2015, 50.1%. SNP vote 2017, 39.9%. But that's not the really telling thing. Tory vote 2015, 5.9%. Tory vote 2017, (an astonishing) 30.5%. Apply what I say above and I think we can at least speculate it will soon be somebody else joining the Caledonian Sleeper.

Next blog, excusing events, I will turn my attention to the Labour Party. North and South.

But, in truth they have four quite separate worries.

The first is that they are aware of a tendency, that I have already alluded to in my previous blog, for Westminster Scottish polling to overstate their support. They themselves realise that constant references to Westminster as a "foreign" parliament, necessary for their wider project, is hardly a strong point when arguing that their supporters must nonetheless turn out to vote in its elections. The big thing about 2017 was not that the opposition Parties gained lots of votes but rather than the SNP lost them. I wouldn't bet on them having got them back.

The second is that they fear being caught in a pincer. They worry on the one hand about leeching votes to the Lib Dems, who are the "quiet life" Party in Scotland promising "no more referendums" but also promising remain. This will lose them no seats directly to the Libs, except obviously Fife NE, but it certainly, under first past the post, sees them losing seats to others. They also worry however about how their own, now more, far more, than 2017, express commitment to Remain will play with the forgotten 38% of Scottish politics. Those who voted leave in 2016, a good one third of whom at least, by most calculation, had voted Yes in 2014. Brexit wasn't really an issue in Scotland in 2017. It will be this time.

Thirdly, they worry about their closeness to the idea of making Jeremy Corbyn Prime Minister. He is not, by any means, the sole reason for Scottish Labour's current unpopularity. He is, nonetheless, exceptionally unpopular. Almost as much in Scotland as in England. And yet given the way the Nats have positioned themselves, the only way now to ensure he never enters Downing Street is to vote for the Tories or the Lib Dems. I bet, given the chance, Nicola would turn back time to adopt the Jo Swinson position of possible support for a Labour Government but never for one led by Corbyn. Then again, as she juggles the nationalist balls in the air, that might risk losing populist votes elsewhere.

And finally, they worry about the weather. Not really extreme weather that would affect all parties equally but just dreich horrible weather. The SNP are blessed, if that's the right word, by some front line supporters who would, to their credit I suppose, walk five miles barefoot through a snowdrift to cast their votes for "Freedum!" But their leadership are acutely aware that they also have more or less a monopoly of those who, on the day, depending on the day, look out the window and might not feel bothered to vote at all. Roll on the sleet.

Now, there remain lots of things to encourage the Nats. Nobody suggests they won't remain Scotland's largest party on 13th December. They have however set the bar so high for themselves, and the stakes are so high for them, that I suspect Nicola would bite your arm off now if offered the deal of a single net gain on 13th December. For she gets what a single net loss would mean.

But I finish with a telling example. In 2017, I highlighted what I described as "secret seats", meaning seats that no-one thought in play but I believed might change hands. A lot of them then did. So here's my 2019 secret seat. Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch and Strathspey. SNP vote 2015, 50.1%. SNP vote 2017, 39.9%. But that's not the really telling thing. Tory vote 2015, 5.9%. Tory vote 2017, (an astonishing) 30.5%. Apply what I say above and I think we can at least speculate it will soon be somebody else joining the Caledonian Sleeper.

Next blog, excusing events, I will turn my attention to the Labour Party. North and South.

Sunday, 3 November 2019

My first election blog.

I say with due modesty that, back in 2017, I wrote a series of blogs, in the last of which I pretty much predicted the result of the 2017 General Election in Scotland. Feel free to look them up. They were written against the received wisdom of the day, even among those equally ill disposed to Scottish Nationalism as am I. Which received wisdom was, like it or lump it, that the Nats would pretty much stand still on their annus miraculis of 2015, when they had taken more or less every seat in Scotland.

In 2017, once the people had spoken however, the proof was in the eating. And received opinion suddenly found itself hungry. 21 seats hungry.

My starting point tonight is pretty much the same. Once again that the "received opinion" of the day, that the Nats will make significant gains, is simply wrong. They will probably stand more or less still but the opening question about the "Scottish" election should not be about how many seats the Scottish Tories will lose but rather about how many they will gain.

Let us start by looking at the polls,

Here is every opinion poll on Westminster voting since 2017. Since I'm assuming an informed readership I'm not bothering with a graphic, just a link, https://www.electoralcalculus.co.uk/polls_scot.html

Now, what does that tell you? Well, first of all, that its a bit odd that in pretty much every poll the SNP percentage exceeds anything they actually got when real people actually voted. Which might suggest sampling error. But also that, even excluding this possibility, that the "nationalist" vote bumps along somewhat short of the infamous 45%. Let along the 49% they got in 2015.

Yes (or whatever) you say, but the Tories are still in the low twenties.As indeed they are. Except that a fair bit of the overall percentage is, in the later polls, given to the Brexit Party. Who in most places won't actually be standing, or at least seriously competing. And where do these voters go in that circumstance? Add, shall we say, 4 points from the Brexit Party to the Tory column and then run the figures again through the electoral calculus own calculating tool, even giving the Nats their supposed 38.9% and the Tories lose precisely four seats. Logically, they would be Ayr, Ochil, Gordon and Stirling.

But in all of them there are particular circumstances in that the Tories came from third place in each in 2017, leaving a significant "unionist" vote in the hands of other Parties , some of such voters we can assume were confused about where to place any anti nationalist tactical vote. I'll be very surprised indeed if the Tories lose Gordon, or Ayr or Ochil this time round. But almost as much to the point, most of the other Scottish Tory seats are just about as safe as any seat is in a four Party system. Solid majorities of around 5,000. or above.

Whereas, and here is where things get really interesting, the second most marginal Scottish Tory seat (Gordon) has a majority of 2,607. No fewer than eighteen SNP seats have smaller majorities.And 22 of under 3,000. Most over Labour (of which more later) but five: North Perth, Lanark, Central Ayrshire, Edinburgh South West and Argyll. over the Tories. I see no reason the Tories won't take four of these. The exception is Edinburgh South West, which is very posh but also very "remainy" and where the incumbent, Joanna Cherry, is, like her or not, a very prominent "remainy" MP.

So, even giving the Nats Stirling the other way, by no means a given, the Tories would be up a net three. Even assuming a UK wide landslide didn't deliver them the three way marginals of Edinburgh North or (God forbid) East Lothian.

Now, before going on to look at the prospects for my own Party, a brief word about the Libs. They are up in both Scottish and UK polls but, except for the four seats they hold and NE Fife, anywhere else their starting point is nowhere. In only two seats beyond these five are they even third. There has been talk of the Tories not really trying in Ross, Cromarty and Skye (where they are second) in the hope of unseating Ian Blackford but, majority 5K plus, I can't see it, much as I would like to. The Libs however will regain NE Fife (SNP Majority 2) at a canter. They might well have have done so already in 2017 but for a returning officer wanting to go to his bed.

And so to Labour, second in 16 of these 22 seats where the SNP Majority is less than 3,000.

Well, the most likely thing is that we'll gain none of them. And, what's more, lose 6 of our existing 7. Possibly East Lothian to the Tories but otherwise all "back" to the SNP.

But, hope springs eternal. Two things might happen. Corbyn might once again enjoy a campaign "surge". In 2017, had we pulled resources from the quixotic attempt to regain Eastwood, we would almost certainly have won half a dozen seats in "proper" greater Glasgow and Lanarkshire. Either Kez was completely campaign deaf or, "once a volunteer", knew exactly what she was doing in that exercise. More sympathetic to "the project" leadership this time at least won't make that "mistake". Alternatively, once it is clear there is no danger of Corbyn actually winning, we might pick up some tactical anti Nat votes in the latter stages of the campaign. Although the polling and by-election results have been terrible, there remains a defiant core vote on which to o be built . That tactical add on simply didn't happen in 2017. Where Labour won, or lost narrowly, the Tory vote actually went up. As indeed did the Labour vote in the seats where the Tories defeated the SNP. If however a "unionist together" phenomena happens, where the Greens choose to stand might prove critical.

Anyway, we'll see.

For the moment my prediction is this. SNP 34 (-1) Tories 17 (+4) Libs 5 (+1) Labour 3 (-4).

But I reserve the right to revisit that as the campaign develops

In 2017, once the people had spoken however, the proof was in the eating. And received opinion suddenly found itself hungry. 21 seats hungry.

My starting point tonight is pretty much the same. Once again that the "received opinion" of the day, that the Nats will make significant gains, is simply wrong. They will probably stand more or less still but the opening question about the "Scottish" election should not be about how many seats the Scottish Tories will lose but rather about how many they will gain.

Let us start by looking at the polls,

Here is every opinion poll on Westminster voting since 2017. Since I'm assuming an informed readership I'm not bothering with a graphic, just a link, https://www.electoralcalculus.co.uk/polls_scot.html

Now, what does that tell you? Well, first of all, that its a bit odd that in pretty much every poll the SNP percentage exceeds anything they actually got when real people actually voted. Which might suggest sampling error. But also that, even excluding this possibility, that the "nationalist" vote bumps along somewhat short of the infamous 45%. Let along the 49% they got in 2015.

Yes (or whatever) you say, but the Tories are still in the low twenties.As indeed they are. Except that a fair bit of the overall percentage is, in the later polls, given to the Brexit Party. Who in most places won't actually be standing, or at least seriously competing. And where do these voters go in that circumstance? Add, shall we say, 4 points from the Brexit Party to the Tory column and then run the figures again through the electoral calculus own calculating tool, even giving the Nats their supposed 38.9% and the Tories lose precisely four seats. Logically, they would be Ayr, Ochil, Gordon and Stirling.

But in all of them there are particular circumstances in that the Tories came from third place in each in 2017, leaving a significant "unionist" vote in the hands of other Parties , some of such voters we can assume were confused about where to place any anti nationalist tactical vote. I'll be very surprised indeed if the Tories lose Gordon, or Ayr or Ochil this time round. But almost as much to the point, most of the other Scottish Tory seats are just about as safe as any seat is in a four Party system. Solid majorities of around 5,000. or above.

Whereas, and here is where things get really interesting, the second most marginal Scottish Tory seat (Gordon) has a majority of 2,607. No fewer than eighteen SNP seats have smaller majorities.And 22 of under 3,000. Most over Labour (of which more later) but five: North Perth, Lanark, Central Ayrshire, Edinburgh South West and Argyll. over the Tories. I see no reason the Tories won't take four of these. The exception is Edinburgh South West, which is very posh but also very "remainy" and where the incumbent, Joanna Cherry, is, like her or not, a very prominent "remainy" MP.

So, even giving the Nats Stirling the other way, by no means a given, the Tories would be up a net three. Even assuming a UK wide landslide didn't deliver them the three way marginals of Edinburgh North or (God forbid) East Lothian.

Now, before going on to look at the prospects for my own Party, a brief word about the Libs. They are up in both Scottish and UK polls but, except for the four seats they hold and NE Fife, anywhere else their starting point is nowhere. In only two seats beyond these five are they even third. There has been talk of the Tories not really trying in Ross, Cromarty and Skye (where they are second) in the hope of unseating Ian Blackford but, majority 5K plus, I can't see it, much as I would like to. The Libs however will regain NE Fife (SNP Majority 2) at a canter. They might well have have done so already in 2017 but for a returning officer wanting to go to his bed.

And so to Labour, second in 16 of these 22 seats where the SNP Majority is less than 3,000.

Well, the most likely thing is that we'll gain none of them. And, what's more, lose 6 of our existing 7. Possibly East Lothian to the Tories but otherwise all "back" to the SNP.

But, hope springs eternal. Two things might happen. Corbyn might once again enjoy a campaign "surge". In 2017, had we pulled resources from the quixotic attempt to regain Eastwood, we would almost certainly have won half a dozen seats in "proper" greater Glasgow and Lanarkshire. Either Kez was completely campaign deaf or, "once a volunteer", knew exactly what she was doing in that exercise. More sympathetic to "the project" leadership this time at least won't make that "mistake". Alternatively, once it is clear there is no danger of Corbyn actually winning, we might pick up some tactical anti Nat votes in the latter stages of the campaign. Although the polling and by-election results have been terrible, there remains a defiant core vote on which to o be built . That tactical add on simply didn't happen in 2017. Where Labour won, or lost narrowly, the Tory vote actually went up. As indeed did the Labour vote in the seats where the Tories defeated the SNP. If however a "unionist together" phenomena happens, where the Greens choose to stand might prove critical.

Anyway, we'll see.

For the moment my prediction is this. SNP 34 (-1) Tories 17 (+4) Libs 5 (+1) Labour 3 (-4).

But I reserve the right to revisit that as the campaign develops

Saturday, 12 October 2019

2021

I've been to busy to do much blogging but to be honest I've also been at a loss as to what to blog about.

I know this is the weekend of the SNP Conference, so there will be once again much puffery about another Independence referendum over the next few days. But it has been clear for months, if not in truth forever, that whether there will be second such vote will depend on the outcome of the next Holyrood election. Which the Nationalists propose to hold in 2021.

And that to be honest suits the SNP. For their wiser heads know that virtually all polling indicates that, currently, they would lose such a contest. That's why they have quietly, last month, introduced the Scottish Elections (Reform) Bill for the precise purpose of postponing for a year the next Scottish General Election. Which, without this legislation, would otherwise be in May 2020.

If Nicola was serious about an early referendum what better way to advance her cause than by seeking and securing an express mandate for it in just over six months? Instead she is running away. The only strategic outcome the SNP leadership seek from their Aberdeen Conference is, for internal Party management reasons, to give the impression they are serious about an early contest when in reality they are quite the opposite.

I'll only say three other things in passing.

The first is to observe that, given it is an open secret that the date of his next court appearance will be 18th November, the Alex Salmond Indictment is likely to be served next week. It would be quite entertaining if that happened during the Conference.

The second is that by the next SNP Conference in the Spring there is every likelihood Salmond's trial will be over. So the possibility that this will be Nicola's last conference as Party leader seems strangely overlooked by the press.

And the third.......I'll come back to the third. For it is connected to my other theme today, inevitably, Brexit.

Predicting the next week is not easy because of the opacity of what is happening in the EU/UK negotiations but there seems at least a possibility that Boris will get a deal. For the purpose of what I say below, I will assume that to be the case.

Boris with a deal is a very different creature from Mrs May with a deal. Those Tory MP's who believe that "No deal" is actually the best outcome are truly small in number. The vast bulk of the "hold outers" on the May deal did so in the belief that someone else could get a better deal. Their problem is that this someone else was......Boris. So that argument goes away. And indeed some of them might actually persuade themselves that Boris's deal is better, although in truth it is at best only likely to be (slightly) different. The killer argument however for more or less all the Tories to get behind a deal is twofold. The alternative to Boris's deal is not no deal. It is extension. And extension leads not to a second referendum (there is still no Commons majority for that) but certainly to a General Election as a result of which a second referendum might become inevitable.

And also, if you think things through, the Tory manifesto at that election would be for the Boris deal, so those still opposed could hardly stand as Tory candidates. Indeed they might not be given any choice in that matter.

So everything says the Tories get behind a deal and while they might lose the DUP in the process they get back almost all the rebels and, it would appear, (this time) peel off sufficient Labour MPs to get the deal through the Commons.

So then what?

Well, obviously an election.

Although when might be a different matter. A done deal requires a sitting Commons to pass the necessary supporting legislation. So dissolution before 31st October seems unlikely. Dissolution after 31st October however takes the date of the Election into December. Never mind how the public might react to Christmas being "spoiled", the prospect of the weather intervening becomes a real prospect, even more so in January and February. Certainly there was a February election in 1974 but it was on the very last day of the month. So my money would be on March. That would also give the Tories the opportunity to promote the more popular of their policies, possibly even setting legislative bear traps for the opposition in the process.

But the other question is what happens to the opposition. Labour will probably stick with Corbyn and resign itself to disastrous defeat. One thing however is certain. If Corbynism, in truth essentially the politics of perpetual opposition, survives the man himself as the dominant strand of internal Labour opinion, then, if there hasn't been a realignment on the centre left before the election, there will most certainly be one afterwards. Even assuming Labour, initially, remains the principal opposition Party in the Commons. Not perhaps a big if but certainly a small if.

But here I come back to where I started, Scottish politics.

The assumption has been that the 2021 Holyrood election will at the very least deliver an SNP plurality and thus a continued Nationalist Government. A fair assumption. For while the nationalists conduct of the devolved administration has been pretty mediocre, as outlined most recently even by their Common Weal allies, Scottish Labour is currently in an unelectable condition, while the Tories remain toxic in urban west central Scotland. Where most people actually live. And the two together as an alternative administration is inconceivable.

My own suspicion is that the more managerial Nats wouldn't mind a 2021 result that denied them the votes for a second referendum (which they fear they would lose), so long as it delivered them the votes to remain in office. They are for playing the long, "inevitability", game.

But realignment would be realignment. A specifically anti populist, fact based, politics of the centre left. The politics of John Smith and Donald Dewar. To actually get things done. That's my third point. And where better to put that to an early test than in Scotland in 2021?

I know this is the weekend of the SNP Conference, so there will be once again much puffery about another Independence referendum over the next few days. But it has been clear for months, if not in truth forever, that whether there will be second such vote will depend on the outcome of the next Holyrood election. Which the Nationalists propose to hold in 2021.

And that to be honest suits the SNP. For their wiser heads know that virtually all polling indicates that, currently, they would lose such a contest. That's why they have quietly, last month, introduced the Scottish Elections (Reform) Bill for the precise purpose of postponing for a year the next Scottish General Election. Which, without this legislation, would otherwise be in May 2020.

If Nicola was serious about an early referendum what better way to advance her cause than by seeking and securing an express mandate for it in just over six months? Instead she is running away. The only strategic outcome the SNP leadership seek from their Aberdeen Conference is, for internal Party management reasons, to give the impression they are serious about an early contest when in reality they are quite the opposite.

I'll only say three other things in passing.

The first is to observe that, given it is an open secret that the date of his next court appearance will be 18th November, the Alex Salmond Indictment is likely to be served next week. It would be quite entertaining if that happened during the Conference.

The second is that by the next SNP Conference in the Spring there is every likelihood Salmond's trial will be over. So the possibility that this will be Nicola's last conference as Party leader seems strangely overlooked by the press.

And the third.......I'll come back to the third. For it is connected to my other theme today, inevitably, Brexit.

Predicting the next week is not easy because of the opacity of what is happening in the EU/UK negotiations but there seems at least a possibility that Boris will get a deal. For the purpose of what I say below, I will assume that to be the case.

Boris with a deal is a very different creature from Mrs May with a deal. Those Tory MP's who believe that "No deal" is actually the best outcome are truly small in number. The vast bulk of the "hold outers" on the May deal did so in the belief that someone else could get a better deal. Their problem is that this someone else was......Boris. So that argument goes away. And indeed some of them might actually persuade themselves that Boris's deal is better, although in truth it is at best only likely to be (slightly) different. The killer argument however for more or less all the Tories to get behind a deal is twofold. The alternative to Boris's deal is not no deal. It is extension. And extension leads not to a second referendum (there is still no Commons majority for that) but certainly to a General Election as a result of which a second referendum might become inevitable.

And also, if you think things through, the Tory manifesto at that election would be for the Boris deal, so those still opposed could hardly stand as Tory candidates. Indeed they might not be given any choice in that matter.

So everything says the Tories get behind a deal and while they might lose the DUP in the process they get back almost all the rebels and, it would appear, (this time) peel off sufficient Labour MPs to get the deal through the Commons.

So then what?

Well, obviously an election.

Although when might be a different matter. A done deal requires a sitting Commons to pass the necessary supporting legislation. So dissolution before 31st October seems unlikely. Dissolution after 31st October however takes the date of the Election into December. Never mind how the public might react to Christmas being "spoiled", the prospect of the weather intervening becomes a real prospect, even more so in January and February. Certainly there was a February election in 1974 but it was on the very last day of the month. So my money would be on March. That would also give the Tories the opportunity to promote the more popular of their policies, possibly even setting legislative bear traps for the opposition in the process.

But the other question is what happens to the opposition. Labour will probably stick with Corbyn and resign itself to disastrous defeat. One thing however is certain. If Corbynism, in truth essentially the politics of perpetual opposition, survives the man himself as the dominant strand of internal Labour opinion, then, if there hasn't been a realignment on the centre left before the election, there will most certainly be one afterwards. Even assuming Labour, initially, remains the principal opposition Party in the Commons. Not perhaps a big if but certainly a small if.

But here I come back to where I started, Scottish politics.

The assumption has been that the 2021 Holyrood election will at the very least deliver an SNP plurality and thus a continued Nationalist Government. A fair assumption. For while the nationalists conduct of the devolved administration has been pretty mediocre, as outlined most recently even by their Common Weal allies, Scottish Labour is currently in an unelectable condition, while the Tories remain toxic in urban west central Scotland. Where most people actually live. And the two together as an alternative administration is inconceivable.

My own suspicion is that the more managerial Nats wouldn't mind a 2021 result that denied them the votes for a second referendum (which they fear they would lose), so long as it delivered them the votes to remain in office. They are for playing the long, "inevitability", game.

But realignment would be realignment. A specifically anti populist, fact based, politics of the centre left. The politics of John Smith and Donald Dewar. To actually get things done. That's my third point. And where better to put that to an early test than in Scotland in 2021?

Saturday, 27 July 2019

Far too long. Far too detailed

I know many people treat Twitter as an echo chamber gravitating towards following others who share their own views and then spending much of their time agreeing with each other. That has never been my objective on the platform. I follow many of quite different views and am happy on occasion to respectfully agree to disagree.

One of those with whom I most often disagree is Henry Hill, @HCH-Hill, the assistant director of the Tory Website, Conservative Home.

It would be fair to say that our politics could hardly be further apart for Henry isn't just a Tory, he is an ardent Brexiteer and, when it comes to Scottish politics, makes no secret of his belief that the Holyrood Parliament should be abolished altogether!

But he is always polite if combative in our exchanges and we rub along friendedly enough. And very occasionally find ourselves in agreement. No more so than when we found ourselves agreeing that you can't explain British politics since the 2017 General Election without understanding how the Fixed Term Parliament Act of 2011 has completely changed the game.

Prior to 2011, peacetime UK Parliaments had a maximum term of five years. But the governing Prime Minister had the right to seek an earlier dissolution from the Queen which was invariably acceded to, theoretically at least unless there was any prospect of another person being able to command a Commons Majority.

Excepting the special circumstances of October 1974, when Labour, although the largest Party the previous February had no majority or route to a majority, and 1979 when the Government "fell", a broad pattern had emerged whereby a Government sensing victory would go to the Country after four years while one fearing defeat held out the full five. As examples of the former, the Tories in 1983 and 1987, New Labour in 2001 and 2005 and of the latter, the Tories in 1997 and Labour in 2010. Of course things didn't always go to as expected, as discovered by Wilson in 1970 and Heath in February 1974. Or indeed more fortuitously as John Major, having put things off to the very last minute in 1992, found himself to his own pleasant surprise (at least initially) re-elected.

Partly because of these latter arbitrary events, most partisans of the two big Parties were happy enough about this but the Liberals and then Liberal Democrats never were, as they felt controlling the date of the next election gave the Prime Minister's Party an unfair advantage. And when they went into coalition in 2010 they had an additional worry. That David Cameron could call a subsequent election at a time of maximum advantage to the Tories and (potentially) maximum disadvantage to them.

So, as part of the coalition agreement, they insisted that Parliament should sit for a fixed term, eventually agreed at five years, although, to be fair to the Libs, their own initial preference had been for four.

By virtue of the Fixed Term Parliament Act, 2011 this then became the law of the land. Crucially, it still is.

There are now only two ways a Parliament can serve a shorter term. The first is where Parliament itself votes for an early election by a two thirds majority and the second is where the Governing administration is defeated in a vote of confidence in the Commons. Crucially, the right of the serving Prime Minister to go directly to the Monarch to seek an early dissolution by "Royal perogative" has been abolished.

So let's look at the two "worked examples" since 2011.

The first is easy. The 2010 Parliament sat for five years and there then was an election as envisaged which the Tories won and not just Labour but the Liberals also lost.

I assume you already know the disastrous consequence of that although that is not an interpretation Henry would share.

However, come 2017, the Tories believed they would benefit from another, early contest. This was a belief shared across the Parties but the principal opposition Parties could hardly concede that, so, when the Tories proposed going down the two thirds majority route, they could hardly demur. As indeed they didn't. Indeed in normal political times, no opposition Party ever could.

I assume you also know the outcome of this Theresa May masterstroke.

But it is in the aftermath of the 2017 election that the impact of the Fixed Term Parliament Act really strikes home.

As you know, after the 2017 election, Mrs May had a (just) functioning majority for day to day Government thanks to her alliance with the DUP. She had however nothing like a majority for her stated Brexit policy of an orderly exit, particularly after the details of her proposed deal with the EU became known.

But, as she tried to get that deal through the commons she was denied a vital weapon, Prior to 2011, it was open to Prime Ministers, assuming they had cabinet support, to declare any vote a vote of confidence. Members sitting in the name of the governing Party had to support it in the knowledge that, if they didn't, there would be an election. An election where they could hardly expect to be allowed to stand again on the governing Party's ticket. For they, expressly, had no confidence in that Government. But Mrs May didn't have that club in her bag. A vote of no confidence under the 2011 Act must be in particular terms and stand alone from any other issue. So the Tory rebels could happily vote against Mrs May's deal and then, nonetheless, keep her, and more significantly her Party, in power by supporting her in any no confidence vote. As was precisely what happened when Labour laid a vote of no confidence after her defeat on the second "meaningful vote".

Which brings us up to today. And Prime Minister Johnson.

And here is where another piece of legislation comes into play. The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. I know this is boring but it is important. Section 20(1) of that Act defines "Exit Day" as 31st October 2019. That date can be amended by virtue of s.20(4) of the same legislation (as it has been twice already) but it can only be amended by a "Minister of the Crown". And, even if an election is called, then "Minister(s) of the Crown" would remain in post unless until removed at the request of the current Prime Minister, who remains in turn in office until he resigns or (less likely) is removed from office by HMQ at the behest of an alternative candidate who can, as he cannot, command a Commons majority. I appreciate this all seems arcane but it is, believe me, really important.

For, assuming we are talking about the here and now, Boris Johnson is now Prime Minister until he is somehow replaced. An election occurring (I'll come back to this), he is still Prime Minister. Even an election resulting in no clear victor, he remains Prime Minister unless he resigns (cf. G. Brown for a few days post the 2010 election). And during all this time, the Ministers of the Crown remain Ministers of the Crown at his recommendation and none of them is ever going to invoke s.20(4) above. So, in summary, if Boris is still Prime Minister on 31st October we are leaving, with or without a deal. Even if he had a damascene conversion to remain, without changing the law, we are leaving with or without a deal.

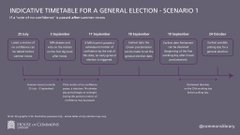

Now, one of my other twitter pals is Kevin Hague @kevverage. He and I are much politically closer than Henry and I. But he does draw some good natured criticism from our side of the constitutional divide for his blind faith in the value of graphs and diagrams. I'm more of a words man but the occasional diagram has its place. So here it is

Alright, basically you can't read it. I get that. So let me tell you what it says. It applies the statutory provisions of the Fixed Term Parliament Act. On the assumption that a vote of no confidence is laid and passed successfully on 3rd September, the first day Parliament returns from recess, the earliest date (by law) on which a General Election could take place is Friday 25th October.

Now, even assuming that happened. Even assuming the election resulted in a landslide victory for the Liberal Democrats, granting them an absolute majority, the timetable for forming an administration, reconvening Parliament and engaging s.20(4) is so tight as to be practically impossible.

In summary, Boris has already run out the straightforward vote of no confidence route to stop a hard Brexit.

But what if he wants to call an election using the two thirds majority route under the 2011 Act, as Mrs May did in 2017? Well, apart from the man himself ruling that out, for the opposition to play ball would be a mug's game. Sure, if he opted for that on 3rd September, the theoretical Lib Dem landslide might just have enough time. But the Lib Dems aren't going to win a landslide and if he's not now proposing to do it all, he's certainly not going to do it on 3rd September. Within a week even the likes of Richard Burgon would work out that "A socialist Labour Government" would only arrive in office already out of the EU. And having conspired at that end, be even more unlikely to ever be arrived at all. So Parliament needs to continue to sit, which an immediate election specifically rules out.

So checkmate to Boris?

In summary, if he is Prime Minister on the date of any Autumn election before or after 31st October, then yes. We are out without a deal even if he loses that election. That is the import of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. Even if we have by then a Government which, given time would repeal it in its entirety. That's the way legislative democracies work.

But there is one way out and it comes back to the Fixed Term Parliament Act.

Section 2 essentially provides that there will be an election called within 14 days if Parliament declares it has no confidence in the Government unless within that 14 day period Parliament declares itself to have confidence in a (by implication alternative) Government.