One of those with whom I most often disagree is Henry Hill, @HCH-Hill, the assistant director of the Tory Website, Conservative Home.

It would be fair to say that our politics could hardly be further apart for Henry isn't just a Tory, he is an ardent Brexiteer and, when it comes to Scottish politics, makes no secret of his belief that the Holyrood Parliament should be abolished altogether!

But he is always polite if combative in our exchanges and we rub along friendedly enough. And very occasionally find ourselves in agreement. No more so than when we found ourselves agreeing that you can't explain British politics since the 2017 General Election without understanding how the Fixed Term Parliament Act of 2011 has completely changed the game.

Prior to 2011, peacetime UK Parliaments had a maximum term of five years. But the governing Prime Minister had the right to seek an earlier dissolution from the Queen which was invariably acceded to, theoretically at least unless there was any prospect of another person being able to command a Commons Majority.

Excepting the special circumstances of October 1974, when Labour, although the largest Party the previous February had no majority or route to a majority, and 1979 when the Government "fell", a broad pattern had emerged whereby a Government sensing victory would go to the Country after four years while one fearing defeat held out the full five. As examples of the former, the Tories in 1983 and 1987, New Labour in 2001 and 2005 and of the latter, the Tories in 1997 and Labour in 2010. Of course things didn't always go to as expected, as discovered by Wilson in 1970 and Heath in February 1974. Or indeed more fortuitously as John Major, having put things off to the very last minute in 1992, found himself to his own pleasant surprise (at least initially) re-elected.

Partly because of these latter arbitrary events, most partisans of the two big Parties were happy enough about this but the Liberals and then Liberal Democrats never were, as they felt controlling the date of the next election gave the Prime Minister's Party an unfair advantage. And when they went into coalition in 2010 they had an additional worry. That David Cameron could call a subsequent election at a time of maximum advantage to the Tories and (potentially) maximum disadvantage to them.

So, as part of the coalition agreement, they insisted that Parliament should sit for a fixed term, eventually agreed at five years, although, to be fair to the Libs, their own initial preference had been for four.

By virtue of the Fixed Term Parliament Act, 2011 this then became the law of the land. Crucially, it still is.

There are now only two ways a Parliament can serve a shorter term. The first is where Parliament itself votes for an early election by a two thirds majority and the second is where the Governing administration is defeated in a vote of confidence in the Commons. Crucially, the right of the serving Prime Minister to go directly to the Monarch to seek an early dissolution by "Royal perogative" has been abolished.

So let's look at the two "worked examples" since 2011.

The first is easy. The 2010 Parliament sat for five years and there then was an election as envisaged which the Tories won and not just Labour but the Liberals also lost.

I assume you already know the disastrous consequence of that although that is not an interpretation Henry would share.

However, come 2017, the Tories believed they would benefit from another, early contest. This was a belief shared across the Parties but the principal opposition Parties could hardly concede that, so, when the Tories proposed going down the two thirds majority route, they could hardly demur. As indeed they didn't. Indeed in normal political times, no opposition Party ever could.

I assume you also know the outcome of this Theresa May masterstroke.

But it is in the aftermath of the 2017 election that the impact of the Fixed Term Parliament Act really strikes home.

As you know, after the 2017 election, Mrs May had a (just) functioning majority for day to day Government thanks to her alliance with the DUP. She had however nothing like a majority for her stated Brexit policy of an orderly exit, particularly after the details of her proposed deal with the EU became known.

But, as she tried to get that deal through the commons she was denied a vital weapon, Prior to 2011, it was open to Prime Ministers, assuming they had cabinet support, to declare any vote a vote of confidence. Members sitting in the name of the governing Party had to support it in the knowledge that, if they didn't, there would be an election. An election where they could hardly expect to be allowed to stand again on the governing Party's ticket. For they, expressly, had no confidence in that Government. But Mrs May didn't have that club in her bag. A vote of no confidence under the 2011 Act must be in particular terms and stand alone from any other issue. So the Tory rebels could happily vote against Mrs May's deal and then, nonetheless, keep her, and more significantly her Party, in power by supporting her in any no confidence vote. As was precisely what happened when Labour laid a vote of no confidence after her defeat on the second "meaningful vote".

Which brings us up to today. And Prime Minister Johnson.

And here is where another piece of legislation comes into play. The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. I know this is boring but it is important. Section 20(1) of that Act defines "Exit Day" as 31st October 2019. That date can be amended by virtue of s.20(4) of the same legislation (as it has been twice already) but it can only be amended by a "Minister of the Crown". And, even if an election is called, then "Minister(s) of the Crown" would remain in post unless until removed at the request of the current Prime Minister, who remains in turn in office until he resigns or (less likely) is removed from office by HMQ at the behest of an alternative candidate who can, as he cannot, command a Commons majority. I appreciate this all seems arcane but it is, believe me, really important.

For, assuming we are talking about the here and now, Boris Johnson is now Prime Minister until he is somehow replaced. An election occurring (I'll come back to this), he is still Prime Minister. Even an election resulting in no clear victor, he remains Prime Minister unless he resigns (cf. G. Brown for a few days post the 2010 election). And during all this time, the Ministers of the Crown remain Ministers of the Crown at his recommendation and none of them is ever going to invoke s.20(4) above. So, in summary, if Boris is still Prime Minister on 31st October we are leaving, with or without a deal. Even if he had a damascene conversion to remain, without changing the law, we are leaving with or without a deal.

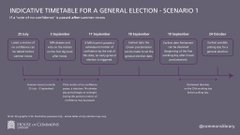

Now, one of my other twitter pals is Kevin Hague @kevverage. He and I are much politically closer than Henry and I. But he does draw some good natured criticism from our side of the constitutional divide for his blind faith in the value of graphs and diagrams. I'm more of a words man but the occasional diagram has its place. So here it is

Alright, basically you can't read it. I get that. So let me tell you what it says. It applies the statutory provisions of the Fixed Term Parliament Act. On the assumption that a vote of no confidence is laid and passed successfully on 3rd September, the first day Parliament returns from recess, the earliest date (by law) on which a General Election could take place is Friday 25th October.

Now, even assuming that happened. Even assuming the election resulted in a landslide victory for the Liberal Democrats, granting them an absolute majority, the timetable for forming an administration, reconvening Parliament and engaging s.20(4) is so tight as to be practically impossible.

In summary, Boris has already run out the straightforward vote of no confidence route to stop a hard Brexit.

But what if he wants to call an election using the two thirds majority route under the 2011 Act, as Mrs May did in 2017? Well, apart from the man himself ruling that out, for the opposition to play ball would be a mug's game. Sure, if he opted for that on 3rd September, the theoretical Lib Dem landslide might just have enough time. But the Lib Dems aren't going to win a landslide and if he's not now proposing to do it all, he's certainly not going to do it on 3rd September. Within a week even the likes of Richard Burgon would work out that "A socialist Labour Government" would only arrive in office already out of the EU. And having conspired at that end, be even more unlikely to ever be arrived at all. So Parliament needs to continue to sit, which an immediate election specifically rules out.

So checkmate to Boris?

In summary, if he is Prime Minister on the date of any Autumn election before or after 31st October, then yes. We are out without a deal even if he loses that election. That is the import of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. Even if we have by then a Government which, given time would repeal it in its entirety. That's the way legislative democracies work.

But there is one way out and it comes back to the Fixed Term Parliament Act.

Section 2 essentially provides that there will be an election called within 14 days if Parliament declares it has no confidence in the Government unless within that 14 day period Parliament declares itself to have confidence in a (by implication alternative) Government.

So suppose we vote down Boris but then declare confidence in somebody else? That somebody would have to be in the Commons, have no interest in a (future) long term occupation of the office of Prime Minister yet be patently capable of discharging the role of PM short term. They would almost certainly have to be a Tory and yet not intend to continue in elected office. They would have no interest in appointing an alternative cabinet let alone a host of junior ministers, Their Government would last no longer than a week with one simple task, to invoke section 20(4) of the Withdrawal Act to declare the "Exit Date" to be some time next year. They wouldn't even have to appoint a full administration to do that. Or even a single Minister of the Crown. For which Minister is better than the Prime Minister? And then, once that was done, they'd declare, as they had in advance of office that they'd happily go down the two thirds majority route for an early election. In which they wouldn't stand and in the aftermath of which they would contentedly stand aside. Their obligation to the Nation done. There is one man who, by now, you have hopefully worked out could fill this role. The Rt. Hon Kenneth Clarke Q.C. M.P.

Now, I'm reasonably sure the Libs and odds and sods remainers would be up for this. Even, for a single vote of confidence, the SNP. But it needs the Labour front bench. About that I'm not so sure. But we'll deal with that if we have to.

Postscript. Since I wrote this a number of others have reached the same conclusion as I do. In the process a number of technical issues have arisen on which it would be appropriate to comment.

The first is what happens to the government and Prime Minister immediately if they lose a vote of confidence? My own view is in practical terms, nothing. The Prime Minister does not have to resign and in my opinion would be daft to do so. The country needs to have a Prime Minister and, if Johnson resigned, the Queen would of necessity have to appoint someone else, even if she knew they did not have a Commons majority. Even if Johnson offered to resign, my inclination is that the Queen would ask him to stay on in a caretaker capacity, a request he could could hardly refuse.

The second is however how a temporary government could come into being, the suggestion that this would draw the Queen into political controversy? I don't agree with this. It wouldn't be for the Queen to pick some random and invite him or her to "have a go". The approach would have to be the other way, with someone who already had the numbers going to the palace with number and verse on that and then inviting Johnson's dismissal and their own appointment. If necessary, the Commons could hold an indicative vote to show that these numbers exist.

It's important however to note that the Fixed Term Parliament Act requires confidence to be expressed within fourteen days in an actual alternative Government and not simply a hypothetical alternative one. So the sequence requires the Temporary PM to have been appointed before the Commons holds that vote.

Thirdly, there is a suggestion this is all a dead duck as the Labour Front Bench won't play ball.

Corbyn's functionaries are certainly saying that publicly. But if any vote of confidence is delayed even by a few days when Parliament returns, any General Election would have to (by law) take place after a hard Brexit. Nobody gets that better than Dominic Cummings. If Labour refused to support a temporary halt to that Brexit eventuality it would be expressly clear that this had been what they had done. The electoral consequences of that for (what remains, just) my Party would be cataclysmic. We could easily be the third Party in any such contest.

So it is, in my opinion, still all game to play for.